- An Essay by Richard Guy Wilson

- An Essay by Mario Buatta

- An Essay by M. Kirby Talley, Jr.

- “Before & After”

“…AS OUR SOCIETY becomes increasingly changed, complicated and diverse, history can offer us an orientation which renders a sense of continuity leading to confidence in community, family and the individual. Our past can unite us. It can allow for all people to become “part of the chorus.”

No type of appreciation of history can evoke more visceral reaction than historic preservation of buildings and landscapes which allows us to truly step back and see, hear and smell the past. Historic preservation encourages people to imagine what those that came before us experienced. It helps us to understand the past and gain vision into what it actually meant to live in times before our own. No effort designed to stimulate an aesthetic insight for yesterday can be more meaningful than encountering history in a visit to a setting of the past made possible by historic preservation.”

Mitch Postel, President

San Mateo County Historical Association

Importance of Historic Preservation

by Richard Guy Wilson

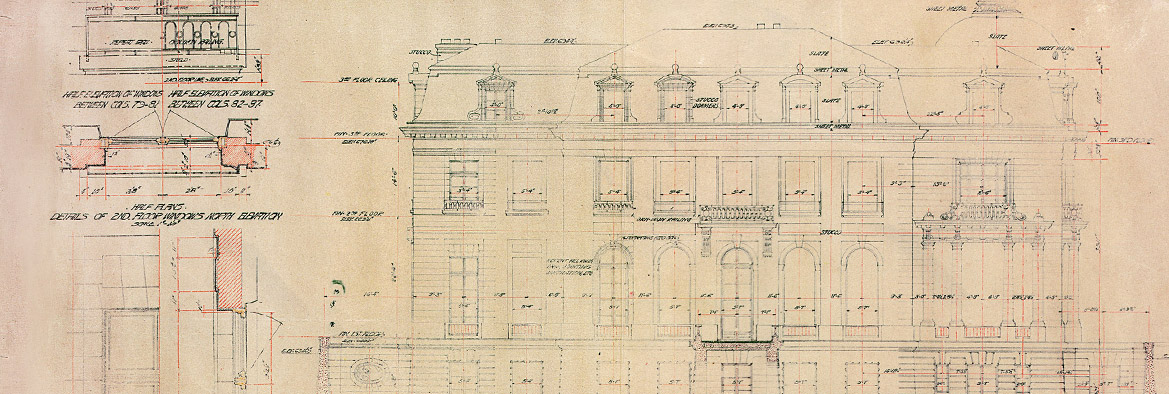

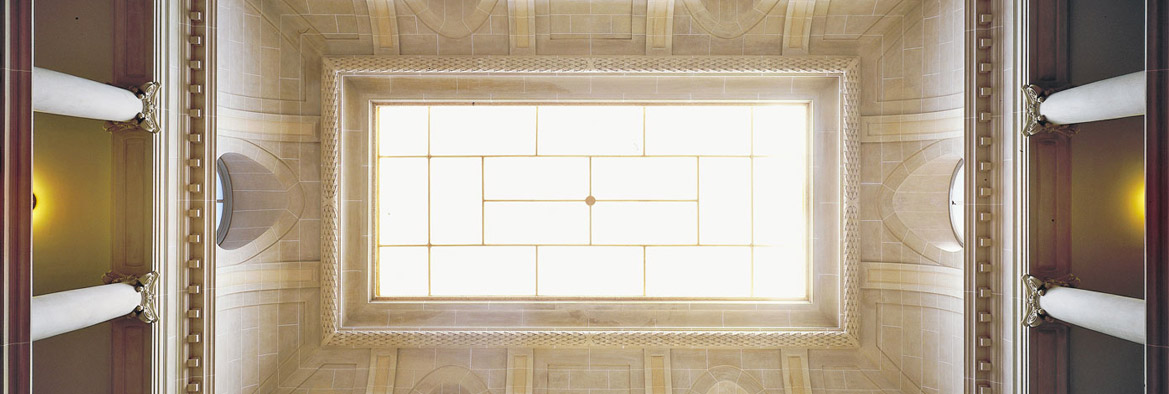

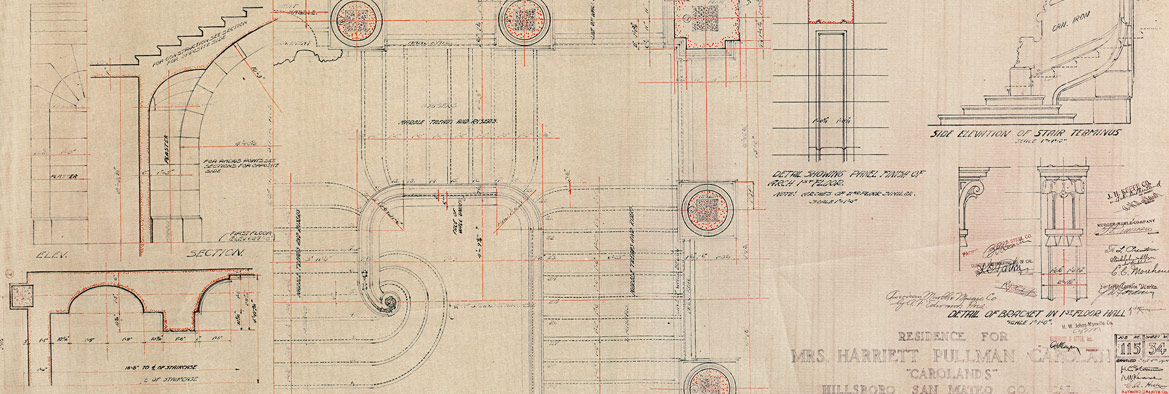

How do we know history or the past? We learn about it in many ways such as books, reading old newspapers, markers along the road, TV, movies, gossip and through first-hand contact. Yes, a photograph or images on your computer can give quick snapshots, but how do we know how big is the house? The experience of actually walking into a great stair hall such as at Carolands cannot be duplicated in photos. Nothing but the actuality of being there can capture the size, the drama, the “wow” effect of actually seeing it, and walking up and down. The same might be said about gardens. They can be photographed, but the slow walk and understanding the sight lines and relation to the house and the hills beyond, and the actual plants, their various leaves and smell cannot be duplicated.

Historic preservation has a long and at times contentious history in the United States. We were a new nation in the nineteenth century lacking the history of the Old World, how could we present ourselves? Dates can be important such as in the 1820s with the looming 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a decision was reached to save and restore Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Founding fathers have always been important and George Washington’s Mount Vernon was saved by a group of ladies in the 1850s from falling further into ruin. One can trace a long history of preserving different buildings of famous individuals throughout the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with projects such as the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in the 1930s, or the moving of structures and creating ghost towns such as Knott’s Berry Farm in California. A shift in the focus, or perhaps an enlargement of what is considered important comes in the 1950s and 60s with the so-called “urban renewal” and also the interstate highway system. Downtowns and main streets were ravaged by new buildings and people moving to the suburbs. What could be saved? Although there had been some previous legislation at both the national and state levels it is the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966 that mandated that all states must take an inventory of their older buildings and select the important ones to save, or at least place them on a national register.

Over the years new perspectives were gained as it became apparent that the houses of mill workers, and the actual mills, along with early gas stations were a part of our history. Open spaces, whether a town square or a common were part of life, and needed to be recognized. And of course there are developers who want to build a new tower and tear down old houses. Not everything of the past can be saved but there is much that can be adapted and put to new uses instead of just demolition.

Carolands of course is a house of former wealth, threatened many times with demolition. But it exemplifies the very best in French design both in the building itself, with its magnificent interiors, and the gardens. It can allow the individual to experience a part of the past, whether you are the master or mistress of the house sitting at your end of the table, or the servant waiting in the wings, you can understand and grasp much better the past and history.

A Note on the Decoration of Carolands

by Mario Buatta

I saw Carolands for the first time in 1991, almost ten years before the Johnsons bought it. The unoccupied building was being used as a designer show house to make money for a local charity. I was able to look past the temporary decorating schemes to see the remarkable though ramshackle Beaux-Arts architecture behind them all. I couldn’t believe that a house of this caliber – a true château – had been left behind to vandals, crumbling for want of maintenance. I wondered: would Carolands remain standing until someone sufficiently romantic and resourceful came along to return it to its original splendor? I hoped so, but I never dreamed I would one day be asked to decorate probably 50 (I never counted) of its rooms.

When Charles and Ann Johnson summoned me to Carolands in 1998, they were ready to take on this noble near-ruin back to its 1917 glory. I was overwhelmed with the scope of restoration work ahead of them but honored to be asked to help with the ultimate decoration. Fortunately I had well over a year to plan ahead, well over a year before a single wall could be painted or a curtain hung.

The ballroom, whose finishing stages were interrupted by the First World War, had been left with bare walls instead of the planned paneling. With the apricot glaze we applied to the newly paneled walls, the ballroom was at last an inviting space. Robert Jackson, the well-known New York decorative artist, came west with six assistants, and was responsible for several of the beautiful new wall finishes at Carolands. No wall at Carolands was simply given a few coats of fresh paint. I brought my team of four fine painters from New York to glaze every space that was not decorated by Jackson or was not some bit of precious bare wood boiserie Mrs. Carolan’s architect had brought from France before the First World War broke out. Also from New York came all the curtains and upholstery, produced in my workrooms.

A Thing of Beauty Is a Joy Forever

by M. Kirby Talley, Jr.

AS KEATS FAMOUSLY PUT IT in his poem Endymion, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.” As a premise in aesthetics this sentiment is correct. Regrettably in the real world, things of beauty, both great and small, are constantly under threat. One needs only to think of World Wars I and II to realise the extent of irreplaceable losses to our built cultural heritage and the contents which graced their interiors.

During World War II entire cities were bombed to dust. The works of brilliant architects and the extraordinarily talented craftsmen who labouriously brought them to life — which sometimes required centuries to complete — were wilfully destroyed in the fiery twinkling of an eye.

John Ruskin, one of the greatest of all writers on art and architecture, saw buildings in The Lamp of Memory in his Seven Lamps of Architecture almost as anthropomorphic objects. “The greatest glory of a building … is in its Age, and in that deep sense of voicefulness, of stern watching, of mysterious sympathy, nay, even of approval or condemnation, which we feel in walls that have long been washed by the passing waves of humanity.” Great buildings stand as sentinels to the ingenuity, creativity, and genius of the human mind, and the desire to achieve a perfect blend of beauty and facility.

While war is the most notorious cause of the destruction of beauty, many others, less dramatic, are just as final. Anyone who saw the 1974 Victoria & Albert Museum exhibition, The Destruction of the Country House, 1875 – 1974, or its catalogue, will not forget the intense sorrow caused by looking at photographs of remarkable buildings and interiors, most of which are completely gone and now only known thanks to these haunting images. Fire destroyed many of these houses, poor location others, owners’ whims quite a few, but lack of finances to maintain such establishments counted for the majority of losses.

The 1974 V & A exhibition spurred a renewed impulse for heritage preservation in Great Britain, already a leader in the field with its renowned privately funded National Trust for England, Wales, and Northern Ireland (1895/1907), and the National Trust for Scotland (1931). In 1983 English Heritage, a governmental organisation, was established. The United States was not far behind Great Britain with John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Colonial Williamsburg (1928/1970), the Preservation Society of Newport County (1945), and the American National Trust for Historic Preservation (1949). Regardless how many such organisations, whether privately or government funded, are now operating around the world, not enough of them exist to keep up with the daily losses to the global international cultural heritage.

We have a tendency to forget just how many private owners of country houses still exist in Britain who manage to maintain their ofttimes immense domiciles filled with irreplaceable treasures. Their preservation achievements have been the result of love for their ancestral homes, and the landscape settings which set them off to such advantage. Most country house owners today realise they are more custodians than owners.

While financial necessity initially forced many of these owners to open their homes to the public, these days most do so with pleasure and an awareness that such beauty and history should be shared. This was eloquently expressed by Paul Mellon, discriminating collector and benefactor par excellence, when he insisted the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., be accessible for all to “enjoy a five minute reverie with beauty.”

Today it has become ever more important for the private sector to step forward and play an active rôle in the preservation of art and architecture — in fact culture in general — an essential undertaking now being increasingly shunned by governments everywhere due to budget cuts and a distressing lack of understanding of the significance of history. If people are denied — for whatever reasons — the opportunity to properly comprehend the whys and ways of the past and how they brought them to where they are, they will never perceive how they should attempt to best proceed into an unknown and uncertain future.

Dr. Ann and Charles Johnson deserve immense praise for their insightful courage and unstinting determination in undertaking the stunning restoration of Château Carolands, one of the largest private residences ever built in America.

Inspiration for Carolands comes from various sources, primary among them Madame de Pompadour’s Château de Bellevue at Meudon, alas torn down in 1823, and the much earlier Château de Maisons by François Mansart, still standing N.W. of Paris. Actual work on Harriett Pullman Carolan’s dream house began in 1914, but the subsequent history of the building project, and the house’s life after Mrs. Carolan, is not an especially joyful story. That saga is captivatingly told in an engaging and highly informative documentary film, Three Women and a Château.

Over the years, this American Château remarkably escaped several close encounters with the wrecker’s ball. Considering the size of the house — 98 rooms in a 67,066 square foot mansion — and its degraded condition, courage again comes readily to mind when Charles and Dr. Ann Johnson bought Carolands in 1998. A meticulous, multi-year restoration was undertaken and in 2012 the Johnsons donated le château des trois dames to the Carolands Foundation. Thanks to their vision and generosity, this masterpiece of Gilded Age American architecture is open to future generations for their delectation and edification.